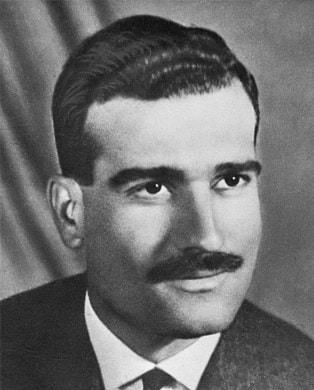

Interest in Eli Cohen boomed after Netflix produced a series about the legendary Israeli spy. Cohen’s success in penetrating the top echelons of the Syrian government remains one of the IDF’s and Mossad’s greatest achievements. But it also highlights a major problem faced by Israel’s spymasters today.

In the 1960s, Israel’s intelligence community could recruit agents from a huge pool of Jews born in Muslim countries. Indeed, more than 700,000 arrived in Israel between 1944 and 1964. Such immigrants were a priceless asset for a nation struggling to survive in a hostile Middle East.

The Egyptian-born Cohen used his flawless language skills and familiarity with Arab culture to operate in Syria under deep cover. Before his assignment, he lived in an Arab village in northern Israel for further training. Later, he was sent to Argentina to reinforce his credentials as a wealthy Arab businessman.

Cohen maintained his cover story in Syria for three years, while building a vast network of contacts among the country’s elites. He was able to accomplish this incredible feat because he was in essence an Arab, albeit a Jewish one. Today, there are hardly any Eli Cohens left.

Young Israelis shun Arabic

Immigration to Israel from the Arab world dried up as most Jews fled en masse. With few exceptions, Israeli Jews born in Muslim countries are either dead or aging by now. Their children fully integrated into Israeli society, and most do not speak Arabic.

Meanwhile, interest in learning the language declined sharply over the years. For most Israeli youngsters, English is a much more appealing and relevant option, while Arabic is often seen as the “enemy’s language.”

The IDF, which relies heavily on Arabic knowledge, initiated programs to encourage high schoolers to study Arabic. These efforts are bearing some fruit, but the number of students who take up high-level Arabic studies remains low.

The IDF and Shin Bet also offer intense Arabic training to recruits earmarked for intelligence and field positions. But faced with a decline in the number of native speakers, Israel’s defense establishment developed a novel approach for producing fluency in the language.

Shin Bet’s Arabic school

The Shin Bet’s unique Arabic program lasts almost a year. During this period, trainees gain in-depth familiarity with all facets of the language, ranging from spoken and written Arabic to slang and religious studies.

In 2017, the Walla! news website offered a rare glimpse into Shin Bet’s language school. The report highlighted the original approach behind the agency’s learning model.

Based on long years of experience, instructors concluded that the best students do not necessarily arrive with previous knowledge of Arabic. As a result, Shin Bet shifted its focus to identifying candidates with an innate talent for studying new languages.

Avi Dichter, a former Shin Bet director and a graduate of the Arabic school, told Walla! about the program’s unorthodox model and impressive results.

“This is super-revolutionary thinking,” Dichter said. Israel’s recruits achieve a higher skill level than foreign intelligence officers who studied Arabic in Lebanon, he said.

No more spies like Eli Cohen?

However, teaching Israeli Jews to read and speak Arabic is not enough. Hence, the IDF also draws on Israeli Arabs who enlist for military service. These soldiers, who are usually Druze or Bedouin — and increasingly also Christian and Muslim — make key contributions in intelligence and operational units.

Still, the number of Arab recruits is low, and not all are fit for the most challenging roles. Meanwhile, Jewish soldiers and agents, regardless of their skill level, cannot blend in and pass the scrutiny that a deep cover agent would face in hostile territory.

This means that Israel’s spy chiefs may have to increasingly rely on foreign partners in order to secure human intelligence from Arab countries. Israel maintains strong security ties with Jordan, and is reportedly also boosting its relations with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. Naturally, these countries can plant agents where Israel cannot.

Israel also compensates for its current limitations with advancements on other fronts. Notably, the intelligence community develops cutting-edge technologies and cyber capabilities to acquire invaluable information.

Still, an old-school, well-placed spy in the enemy’s corridors of power can uncover secrets that would otherwise remain elusive. It may be hard to admit this, but Israel may never again be able to run an agent like Eli Cohen in the heart of an Arab capital.